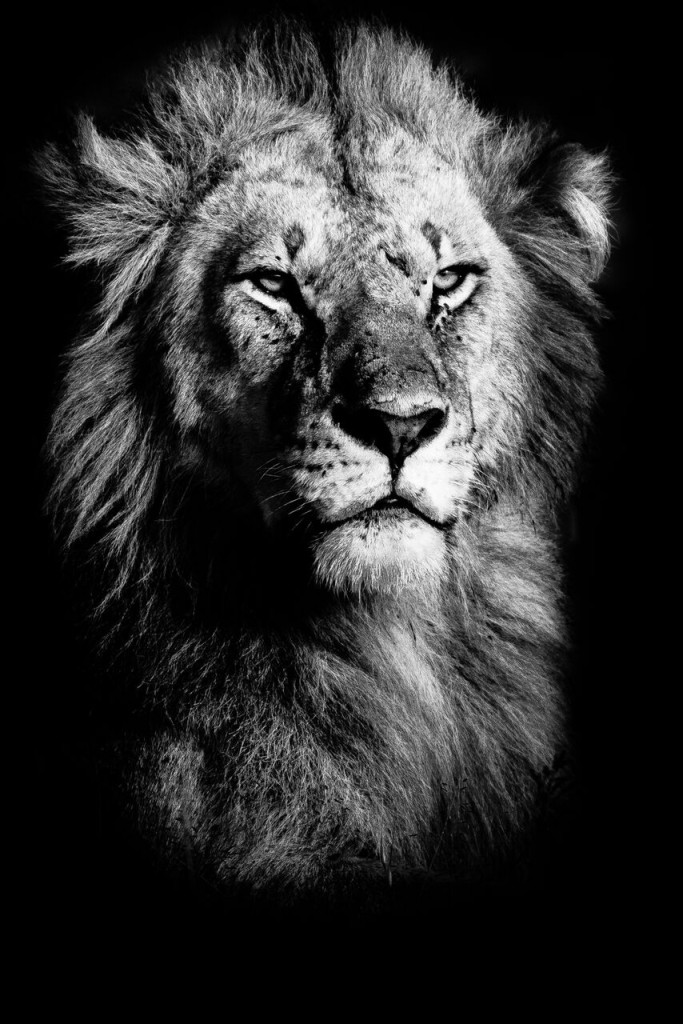

Asilia in the Land of Lions

If there’s one animal, above all others that the first-time safari-goer (and come to that the second, third or fourth time safari-goer) wants to see it has to be the lion.

The Lion: Everyone’s Favorite

Alongside elephants, there is perhaps no other animal so immediately associated with an African safari as the King of the Jungle, or more correctly, the King of the Savannah. Lions can be seen in most of the savannah parks of East Africa with Tanzania’s Selous, Ruaha, and Tarangire parks being especially well regarded for lions. But it’s the Serengeti that is the real home of the lion and no part of the Serengeti is better regarded for lions and other big cats than the Namiri Plains in the eastern part of the park.

The Namiri Plains are the Serengeti of the imagination. Open, golden grasslands pock-marked with the occasional flat-topped acacia tree stretching as far as you can see. Closed to all but scientists for twenty years in order to allow big cats to thrive undisturbed, the area was finally opened for safaris in 2014 when the Tanzanian National Parks Authority asked Asilia to open a small, low-key camp here. Namiri Plains has since gained a reputation as one of the best camps in East Africa and the place to have a pristine Serengeti experience without the bother of other safari vehicles.

Trouble in Paradise

Driving around the Namiri Plains from one memorable cat sighting to the next it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that all is well with the world, but the truth is that lions are in trouble. Big trouble.

As large, powerful and potentially very dangerous apex predators, lions are adivisive animal. For someone in Europe or America watching them on a TV documentary these are graceful, awe-inspiring creatures to be preserved at all costs, but for a villager in Africa who has to live side by side with lions and have the risk, however small that might be, that a lion will take the livestock they depend upon or, worse still, their child on the way to school, then lions are not so fondly looked upon. And, because of this, just as was done to large predators in Europe and North America, as the human population in Africa has grown over the past century and human-lion conflict increased, so lions have been persecuted.

They’re shot at, speared and, the most efficient technique of all, poisoned (along with anything else that eats the poison-laced carcass laid out as a trap for the lions). This kind of reduction of lion numbers receives a lot of media attention, as does the paid-for trophy hunting of lions by western hunters but the real threat to African lions isn’t from direct killing by humans. It’s through habitat loss.

Reducing Human-Wildlife Conflict

There are numerous ways that human-lion conflict can be cheaply and effectively reduced. These range from better night time protection of cattle in predator-proof bomas (fenced compounds used to keep the livestock in at night) and having adults rather than children guard the livestock when out grazing in the daytime, to changing cultural values, the paying of compensation when livestock and people are attacked and ensuring that local people gain financially from the presence of big cats in their neighbourhood (which creates a higher level of tolerance for lions and other large mammals).

Habitat loss though is a much harder nut to crack. In 1900 the entire human population of Africa was around 133 million, which is roughly the same as the population of Japan today – a country that covers 378,000km2 compared to Africa’s 30.22 million km2. Today, though, the population of Africa is 1.186 billion. All those extra mouths require a lot more food which means a lot more land has to be devoted to agriculture, which in turn means a lot less space for wildlife – and lions need a lot of space.

Additional Factors Affecting Lion Populations

The issue is only going to get worse as by 2050; it’s estimated that the human population of Africa will have reached 2.477 billion. Solving the problem of a fast-expanding human population and the habitat loss associated with it is, alongside climate change, the biggest issue conservationists in Africa are likely to face this century.

Another increasing threat to lions comes, ironically, from the disappearance of tigers. Tiger body parts have frequently been used in traditional Chinese medications, but this trade, along with human-tiger conflict and severe habitat loss, have brought tiger numbers down to the point that the IUCN now classifies tigers as endangered, and as the tigers have become harder to find so the Chinese medicine market has started to turn instead to lions.

It’s not all bad news, though. Lion populations have recently risen in Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe and South Africa and, throughout their range areas; the most important lion populations are in well-protected parks popular with tourists. The money generated through safari tourism to see these lions is the crucial incentive that national governments and landowners need to help keep those lions safe. But even without any real protection lions can still survive as was demonstrated in February 2016 when scientists announced the discovery of a completely new and unexpected population of lions living along the borders of north-west Ethiopia and south-east Sudan.

While the problems facing lions, particularly habitat loss, can seem almost insurmountable there are some glimmers of hope. It’s been suggested that as Africa becomes ever more urban, that rural areas will actually become more and more depopulated as people move to towns and cities in search of work and as people move away this will leave more space for wildlife. Another, small but very significant step, has been the creation of community conservancies such as the Naboisho Conservancy fringing Kenya’s Maasai Mara, where Asilia has two camps. These conservancies work to protect wild landscapes and the animals that live there while giving a regular income to local communities.

The next twenty years will probably be critical to the future of lions (and many other large mammals) in Africa. We can close our eyes to the problem and let lions go the way of the Dodo or we can do what we can to help them. And one of the most effective ways of helping them is by supporting sustainable conservation efforts and local economies primarily in the form of tourism efforts. We look forward to showing you the lions of East Africa…

——

Want to join us? Get in touch with your trusted travel agent or make an enquiry with us below.

More Positive Impact Articles

Electric Vehicles: The Future Of East African Safari Travel?

12 January 2020October 2019 saw the arrival of our first electric, solar-powered safari vehi...

Its Our 15th Birthday: Celebrating 15 Years of Making a Genuine Difference

08 November 2019This year, we're celebrating our 15th birthday and commemorating 15 years of...

World Tourism Awards 2019: Asilia Recognised For Our Positive Impact

01 November 2019The World Tourism Awards acknowledge, reward, and celebrate excellence across...

Supersized Traditional Maasai Necklace

21 October 2019In 2009, we became a founding member of the Mara Naboisho Conservancy and sin...