Meeting the Enemy

Poachers. As a word, it brings to mind organised crime networks with automatic weapons butchering elephants and rhinos for their tusks and horn. But poaching actually comes in many different shades. Is the man who, without a licence, sneakily catches a couple of carp from a private fishing lake in Europe a poacher? Or what about the hunter who illegally traps a rabbit for the pot?

What exactly is a Poacher nowadays?

In the past, I’ve camped in the forests of Central Africa with a group of BaAka (pygmies to you and me) during one of their frequent hunting expeditions. They were after the small duiker forest antelopes and the hunting was taking place on the edge, and perhaps just inside, a protected forest. Was it poaching? Technically, but then again they’ve been doing the same for hundreds of years with no ill effect on the forest eco-system. Actually, the large international conservation NGO who were acting as guardians of the forest at the time helped organise my stay saying that it was important that the BaAka benefit in some manner from what was, essentially, their land.

Then there’s the villager living on the financial edge in East Africa who one day finds a stranger offering him several hundred dollars to shoot that elephant that raids his crops every other night. With the money offered that man can put his children through school and food on his table for more than a year. So, is he the poacher or is it the middle man who makes it all possible, but never actually shoots an elephant himself? Already you can see how the term poacher is starting to look a little less clear cut.

Talking to Those Who Know

As I travelled around northern Tanzania, learning what it took to be an Asilia wildlife guide at Tarangire National Park and following enormous herds of wildebeest through the southern Serengeti, I asked many different people to tell me who qualified as a poacher and, perhaps not surprisingly, I had as many different responses as there are shades of grey. But again and again, though one word kept cropping up. The Kuria. You must go and talk to the Kuria people.

The Kuria (Koria, Wakuria, Abakuria) peoples number around a million and are spread almost equally between Kenya and Tanzania where their homeland is centred on the area between Lake Victoria in the west and the Serengeti and Maasai Mara in the east. Once almost entirely a pastoralist people they are now, as often as not, settled subsistence farmers tending to small shambas (farmsteads) on the lush green hills to the west of the Serengeti. But although they know it’s good to eat greens there’s nothing they really like more than getting their teeth into a good hunk of meat. But, when I say meat, I don’t mean cows and goats. I mean wildebeest. The Kuria people have long been renowned hunters of what is today commonly termed as ‘bush meat’ and it’s a tradition that continues to this very day with an estimated 70,000-130,000 wildebeest being poached every year from in and around the Serengeti eco-system.

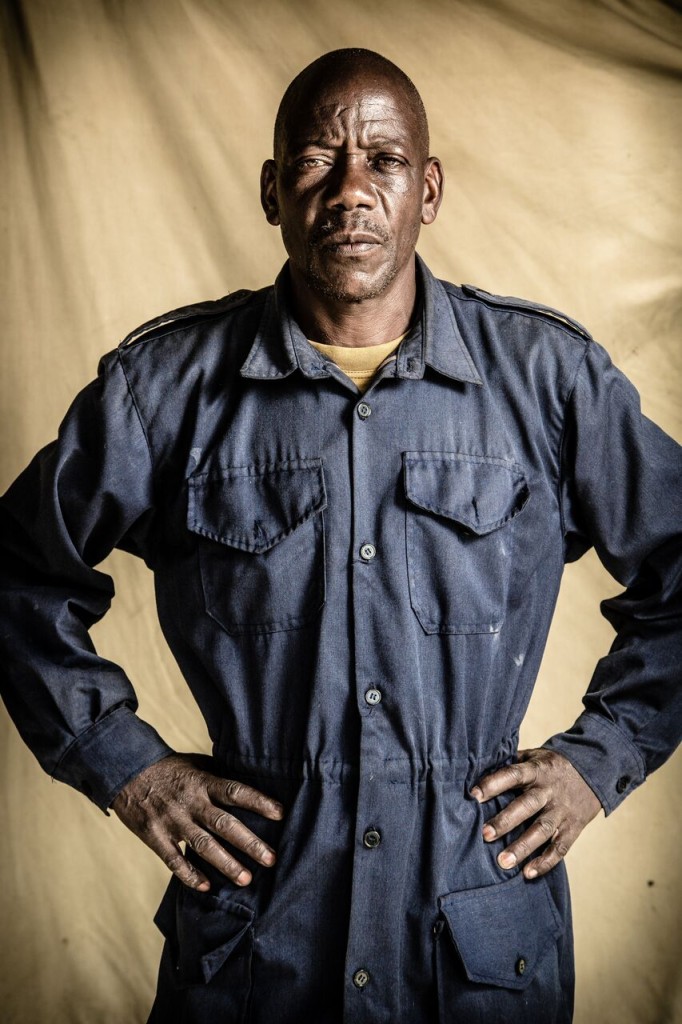

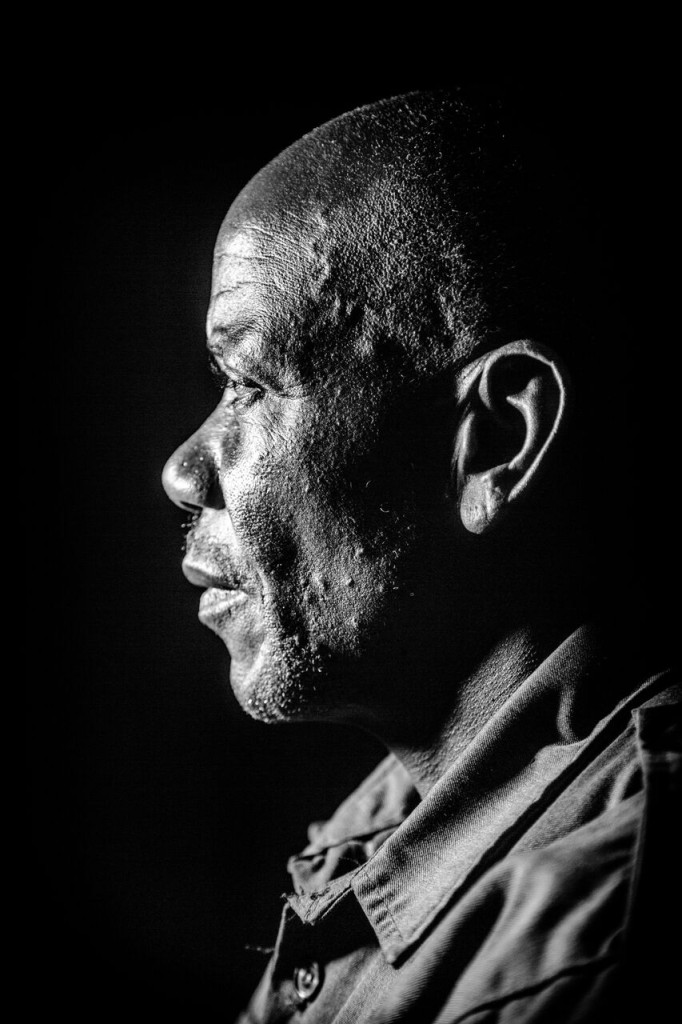

John Mwekwiba is from Mbalimbali village, which, as I discovered when I drove there to meet him, is more a spreading collection of small farms centred on a school and a couple of garishly painted dukas (shops) selling sodas, mobile phone scratch cards, lengths of rope and farming implements. Grabbing a lime soda each we sat down together to talk hunting. John was, like almost everyone in Mbalimbali, Kuria and like most of the men over the age of about thirty-five he had once been a hunter.

Poaching – Then vs. Now

He started hunting in the 1970’s and he told me how his favourite hunting area was down by the Mara River where animals would come to drink. He and his accomplices would dig a long pit, about a hundred metres in length and a couple of metres deep, close to the river. The pit would be lined with sharpened sticks pointing upwards like crocodile teeth and then the whole pit was covered over with twigs and grass so the animals couldn’t see it. When a suitable herd of animals was spotted approaching the river, John and the rest of his team would get behind them and hustle and chase the animals down toward the river. As soon the wildebeest stood on the trap the twigs and grasses would give way and the animals would plunge down and spear themselves on the sharpened sticks. This method of hunting was, I was assured, highly effective and they could take dozens of wildebeest and antelopes at a time. However, setting such a trap took time and it made the hunters obvious to rangers.

Eventually, as anti-poaching patrols and techniques increased and improved, the Kuria had to largely abandon the trap-door method of wildebeest hunting and move instead to the more subtle technique of setting snares. This was, and still is, done by removing the very thin but strong, string-like cord from old car and truck tyres and tying it loosely between a couple of trees at about wildebeest throat height. Then, using the same herding technique as was employed with the pits, the men funnelled groups of wildebeest towards the trees. As the wildebeest ran between the gaps in the trees they’d get the cord twisted around their necks and legs and become trapped after which it was easy to kill them. The snares though were not as effective as the pits and John couldn’t catch as many animals in one go. “With the pits the most animals we ever caught at one time was fifty animals of all different kinds, but with the snares maybe it was only ten animals”, said John in a matter of fact kind of way. I asked him what happened once they’d caught the wildebeest, “Some of the meat was sold to pay for other food, school fees and clothing, but mostly we just ate it with our families and if we did sell any it was only sold within the village for our own community. The skin we would just leave for the hyenas”.

Hunting in the 1970’s, when there were few rangers in the Serengeti, was easier than now, but it was still no walk in the proverbial park. Air patrols by rangers were always a danger but most of the time, if the hunters lay down in the undergrowth, they wouldn’t be seen by the rangers. The risk was if they were wearing a watch or had a spear that could reflect the sunlight, so when they heard a plane or helicopter coming they had to cover any metallic objects up.

Dangers in the Bush

Even so, they were sometimes found and though John always eluded capture, many of his friends were caught and served time (a few months or a year or two) in jail. Generally, after they’d been in jail, they didn’t return to hunting again. Perhaps a bigger danger than rangers came from the Serengeti wildlife itself and John told me how he’d heard of many people being killed by buffalo when they’d stumble unexpectedly into them in patches of woodland. John recalled how one night he nearly became dinner to a lion. He was walking with a wildebeest carcas slung over his shoulder. It was heavy and restricted his vision and a lion stalked up behind him and tried to grab the wildebeest off him, but his friends saw it at the last second and chased it away. Another time, he said, an elephant went on the rampage in their camp; stamping and trampling over everything and that he was lucky to get away from it without being crushed.

Almost ever since the Kuria arrived in this part of Tanzania they’ve hunted wildebeest and other animals for their own consumption, and for years it wasn’t really an issue, but then, one morning, they woke up to find rules had changed and anyone who went hunting would now be classed as a poacher. What had John thought of this? Did he consider himself a poacher or a hunter? “I’m not a poacher. I’m a hunter, but today there are people with guns killing the wildebeest and they are poachers. We never hunted elephants either. No Kuria would do that because we don’t eat elephant meat”.

From afar it sounded like John had lived an exciting, perhaps almost glamorous, lifestyle and now that he made a living working at a safari camp walking guests safely back to their tent at night, I wondered if he missed his hunting days. John smiled at the question, “No, I have no desire to go back to that time. I don’t want my children to do this either. I want them to get an education and do something different”.

John’s answer about his not being interested in hunting anymore was the typical response of most of the people I questioned in Mbalimbali and, even though tens of thousands of wildebeest are still taken each year, the overall levels and support for hunting seems to be dropping. For a start, the government are far tougher on it now, but in the area where John lives anyway, perhaps a bigger reason for this decline in interest is tourism.

Safari companies like Asilia actively look to employ men like John. The company values their bush knowledge and the ex-hunters value a steady wage and the chance this gives them to plan, save and invest in their children’s health and education. “Before, in the north-west of the Serengeti, there was nothing”, John continued, “And with not many camps we had nothing else to do but hunt. But now it’s different. Places, where we used to hide and wait for the wildebeest now, have camps built on them because they have the best view points. Most people here are happy that things have changed because now we make more money from working in the camps than hunting”.

As our conversation came to an end, I glanced over the mud road to the small butchery shop where nothing more sinister than a goat or two was hanging on the hooks. Things are changing indeed for the Kuria.

The post Meeting the Enemy appeared first on Asilia Africa.

More Positive Impact Articles

Electric Vehicles: The Future Of East African Safari Travel?

12 January 2020October 2019 saw the arrival of our first electric, solar-powered safari vehi...

Its Our 15th Birthday: Celebrating 15 Years of Making a Genuine Difference

08 November 2019This year, we're celebrating our 15th birthday and commemorating 15 years of...

World Tourism Awards 2019: Asilia Recognised For Our Positive Impact

01 November 2019The World Tourism Awards acknowledge, reward, and celebrate excellence across...

Supersized Traditional Maasai Necklace

21 October 2019In 2009, we became a founding member of the Mara Naboisho Conservancy and sin...