Just Add Water

There are no truer words than ‘God bless the rains down in Africa’, for as the first major storm breaks, water flows like glistening tears of joy across the wrinkled cheeks of a parched Serengeti.

A dramatic afternoon rain squall moves across the open Serengeti plains.

Namiri Plains

The result of this deluge triggered one of the most special experiences we have ever had in a lifetime of photographing the planet’s most iconic wildlife, on all seven continents.

Staying in Asilia Africa’s Namiri Plains, in the central Serengeti, gave us the incredibly privileged opportunity to watch from start to end the passage of the Great Migration in a magnificent setting, and practically all on our own.

On our arrival, the magnificent endless plains after which the Serengeti is named, were devoid of the ubiquitous herds of wildebeest and zebra. Despite this, there was still plenty of predator activity with at least four to five different lion or cheetah sightings each day. Quite simply, in all of our African travels, the Namiri Plains area is hard to beat when it comes to the opportunity to see or photograph these two iconic cats.

There is an abundance of lion and cheetah residing in the grasslands around Namiri Plains.

The Great Migration

We were however hopeful that our stay would coincide with the coming of the great herds.

Just how big these herds are is anyone’s guess. Some say 1.5 million animals, some say three million, some say far more… What is for sure, is that with the coming of the rain, came the nomads.

Whilst each day brought a glut of predator sightings, our objective remained spending each moment searching for those first dark ribbons of moving bodies. Suddenly, on the second day after the heavy rain, the first pioneers hove into view as tiny specks on a shimmering horizon.

As more rain again fell, the numbers swelled in response. First there were hundreds, and then thousands of zebra that filled the meandering valleys.

A herd of zebra mark the start of the arriving Migration, slowly filling the surrounding plains.

Soon the real sea of bodies appeared from the south, stretching many dozens of kilometres from the woodlands of Ndutu right through to the aptly named Zebra Kopjes. We gazed upon hundreds of thousands of wildebeest and zebra dotting the horizon, sprinkled like raisins over the endless undulating plains. This was the arrival of the Great Migration, passing through the south-central Serengeti on its journey northwards.

From dozens of kilometres away these restless nomads had watched and smelt the rains that triggered their mass exodus from a grazed landscape to a soon-to-be ripening emerald one filled with new shoots of nutritious palatable grasses. Apparently, the herds can hear the storms from over 50km away, and, when closer, they are able to smell the rain that triggers an unflinching determination to get to the drenched landscape.

The herds of the Migration are driven by the rain and the fresh grazing it produces.

Cats on kopjes

Many have waxed lyrical about this sight, but words cannot truly express the emotion at seeing and experiencing such an explosion of animal life in an uncrowded environment that so embodies what a wonderful continent Africa is. Comparable only to South Africa’s sardine run, or a walk along South Georgia Island’s mammal and penguin packed St Andrews Bay beach, this monumental movement of bodies has no terrestrial equivalent.

And with the prey, come the predators. Suddenly so many of the previously uninhabited kopjes now had lion on them, sitting sentinel-like as they scanned the freckled horizon, knowing that the coming of the night would present a buffet of opportunity.

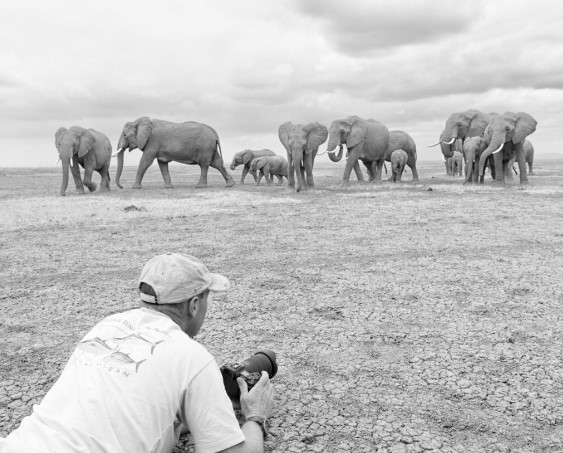

Photographically, like stepping ashore to a half a million strong penguin colony on a South Georgia beach, the scene is overwhelming. It is simply not possible to capture an image of a 360-degree horizon-to-horizon sea of animals, and one is best advised to focus on key features that give a snapshot of the story of instinct, sustenance, and survival.

Our objective from the start was to seek out some of the more picturesque of the kopjes that dot the horizon at regular intervals from our Namiri Plains base. Our hope was to find one of these great cats sitting atop a kopje, surveying the landscape, or considering an opportunity to hunt.

In this respect, we were spoiled for choice. Kopje after kopje had a resident of tooth and claw, some adorned with golden manes, and some wearing spots. The greatest difficulty was to choose whether to stay with what we had found or be lured by the ever-present temptation of literal greener grass calling you siren-like to the next kopje, hoping for an even more prominently positioned cat.

The landscape of Namiri Plains is dotted with granite kopjes, loved by cats for the warm vantage point they offer over the surrounding plains.

Planning the shot

As easy as it was to find a lion or cheetah on one of the beautiful granite slabs that adorn the Namiri area, the difficulty came in finding the perfect kopje. Devoid of clutter, architecturally strong, and aesthetically pleasing to allow an unbroken flow from rock to landscape falling away into the distance.

The final added challenge in creating a truly exceptional and unique artwork is to artistically combine all the other components of this amazing story into one scene that is pleasing on the eye.

Fortunately, after scouting out literally dozens and dozens of kopjes over hundreds of square kilometres, we found a few that had a pleasing architectural feel to them. One rock in particular showcased the depth and distance of the area by being positioned atop of a plateau that gave the sense of looking down into the undulating plains below.

If possible, it was my hope to have a background sprinkled with a herd of wildebeest, something the trained eye would immediately associate with the migration, giving a sense of the regal predator and its prospective prey.

To provide mood, we had planned to be in the area with the rains, which would bring the chance of dramatic skies. And, if we were lucky, we would be able to position ourselves to include a distant rainsquall, as Nick Brandt had so wonderfully achieved with his “Lion with Monolith” work created more than a decade before.

"Lion with Monolith", by Nick Brandt

Combining all these components requires planning, anticipation, and luck. To bring them all together is never easy, but of course the biggest challenge is to find a wild male lion sitting, or even better, standing, atop the rock, regally surveying this beautiful stage, with all other elements simultaneously falling into place.

I cannot tell you how many hundreds of times I have pleaded for a predator, tusker, raptor or other to sit atop of a certain rock, walk through a spot lit corridor, or follow a route I had patiently positioned myself on, knowing it would create a beautiful scene, only to be disappointed when my subject did the exact opposite.

On this particular morning, we had already had four different lion sightings and three different cheetah sightings, all in the space of two hours. Each sighting had been worthy of sitting with and waiting to see what would transpire, but each was ignored in my single-minded, and at times questionable, pursuit of my objective.

Finally, after scouting the many kopjes, we arrived at one of my three favourites, and there sitting 50 meters away, were two magnificent male lions we had seen several times over the preceding days.

It was now 08h30 in the morning and, with the coming of the great herds of wildebeest, came the flies. Millions of them. Coupled with the flies, came the sun, and for lions lounging out in the open, these two factors are a call to move.

A male lion shows his displeasure at the relentless attention received from flies.

A waiting game

Eyeing out my chosen rock, I prayed they would go towards it as they had sat at its base not three days earlier.

The first male got up and walked right past the rock to a medium sized Acacia tree that offered shade. This was not part of my plan, and I knew he would in all likelihood sleep there all day. Nevertheless, we followed him and sat with him for around ten minutes, watching him intermittently swatting flies, giving us hope that he would move again.

Then his companion got up and walked towards the shade close to the kopje. He momentarily disappeared out of view, so we decided to check out where he went. Coming round the blind side of the rock, we suddenly saw that he was not at the base but, unbelievably, going up it to the rock’s summit.

Panic broke out and our very tolerant guide, Ngimba, was besieged with my calls to go this way, then that, two meters forward, try to position for that cloud, can we go a tiny bit closer, no, further away looks better.

No sooner had this magnificent male alighted the rock than his brother in arms decided to join him by scrambling clumsily up the rock face with his powerful claws chewing at the granite like chalk grating a chalkboard.

Sitting atop this beautiful dome of granite were now, not one, but two magnificent male lions. For the next eight hours we photographed them from every conceivable angle.

From the top of the kopje, these two male lions can escape the worst of the flies whilst surveying the surrounding plains.

Patience pays off

Unbelievably however, at no time did they ever stand up together, or do anything in unison other than sleep.

As the afternoon progressed, so too the sky began to build with cumulonimbus clouds swelling all around us, adding wonderful mood and the anticipation of rain. The scene was magnificent with the open plains of the Serengeti, partially laden with the first major herds of wildebeest, acting as a layered story completing the backdrop.

At around 16h30, one of the males left the rock causing the other to become more active.

This change in behaviour was just as just as the sky was building into its most beautiful state, with a distant storm and deluge of rain adding drama to the scene.

On perfect cue, just as we had positioned ourselves to create separation between the kopje and foreground whilst including all aspects of the story above and around him, he stood up, and, akin to the famous scene from The Lion King, he gazed out over his kingdom.

One of the male lions finally delivers the positioning, as the elements align for the perfect shot.

Quite simply we could not have wished for a better opportunity to create a work celebrating Africa’s greatest cat, surveying the continent’s most famous natural spectacle from this beautiful granite throne, enhanced by moody elements.

A huge thank you is due to our guide, Ngimba, whose enthusiasm, patience and understanding during our time at Namiri was instrumental in setting up this opportunity to showcase this wonderful scene that we were now so privileged to be able to share.

Chris Fallows

I have had the almost unparalleled privilege to experience iconic wildlife in a way few people have ever had. My aim is to honour this privilege by creating some of the world’s finest wildlife fine art that does justice to my iconic subjects. I wish to create works of art that are not only aesthetically pleasing, but also have meaning and are a contribution to change.

I have had the almost unparalleled privilege to experience iconic wildlife in a way few people have ever had. My aim is to honour this privilege by creating some of the world’s finest wildlife fine art that does justice to my iconic subjects. I wish to create works of art that are not only aesthetically pleasing, but also have meaning and are a contribution to change.

More Wildlife & Conservation Articles

Leopard vs Cheetah : Can You Tell The Difference

01 April 2020How often do you mistake a leopard for a cheetah or vice versa? I’m sure we’v...

What’s the difference? National Parks, Game Reserves, and Conservancies in East Africa

02 February 2020To most of us, a national park, game reserve, or conservancy are all the same...

Electric Vehicles: The Future Of East African Safari Travel?

12 January 2020October 2019 saw the arrival of our first electric, solar-powered safari vehi...

Guest Gallery: The Serengeti At Its Best

27 November 2019We recently had the pleasure of welcoming guests, Chris and Monique Fallows t...